By Catherine Austin Fitts

I have long been remiss in educating myself about Operation Gladio. For those not familiar with it, here is the description from Wikispooks:

Operation Gladio first came to light in Italy in 1990, after over 40 years of clandestine operations. Members of the project revealed that similar projects existed in most if not all countries of Western Europe. These stay-behind networks were, in essence, super secret armies in at least 14 European countries, which were kept secret from the official governmental structures of the host countries – being controlled by other forces such as the CIA and MI6. They remained mostly dormant but were also involved in anti-communist activities including anti-democratic agitation and false flag “terrorism”. The name Gladio, (or ‘Sword’ in Italian) was technically the name given to their operations in Italy, but has since come by extension to stand for the phenomenon as a whole. Evidence of such arrangements, which had been kept secret from both public and politicians democratically elected governments in the host countries for a quarter of a century was revealed through a series of scandalous revelations in Italy and other NATO countries during the 90s, and meticulously documented by Swiss historian Daniele Ganser in his 2004 book NATO’s Secret Armies. The evidence contained in Ganser’s book, of terrorism directed against the people by secret armies funded and organized by NATO and answerable to deep state elements within NATO, MI6 and the CIA rather than the respective governments is so shocking that the initial reaction of most people would be to reject it. And yet the claims have been substantiated by juridical inquiries in Italy, Switzerland and Belgium and have been debated (and condemned) in the European Parliament.

The first time I put Operation Gladio on my list to research was when I read Christopher Simpson’s description in Blowback of the Dulles brothers working out of Sullivan & Cromwell after WW II and before the passage of the CIA Act of 1949. Simpson reported that they used WW II seized assets in the Exchange Stabilization Fund to respond to the Vatican’s request to help rig elections in Europe.

When I was in Switzerland early last year to interview Thomas Meyer, he was preparing for a conference with Swiss historian Daniele Ganser. At that time I ordered Ganser’s book, as well as several others published since. They have been sitting in my “read first pile” of approximately 350 books.

This Spring, I went road tripping with Thomas from Basel to Copenhagen. We ended up being followed for our visit at the Danish National Museum in a experience I can only describe as comical. I was convinced our “spy” was a private security firm employee. Thomas and his party continued on his speaking tour. I remained in Copenhagen for one more day as I had always wanted to see the city. Unfortunately, I was followed, this time by a couple who appeared to be government employees. I cancelled my sightseeing and worked in the hotel instead. As I worked, I kept being interrupted by emails from my airlines which mysteriously changed my ticket the next day three times, with the final change routing me on an alternative airline through NATO HQ – an utterly nonsensical itinerary. I booked a new ticket on a different airline and flew back to Switzerland the next day, resolved to educate myself about NATO and Operation Gladio.

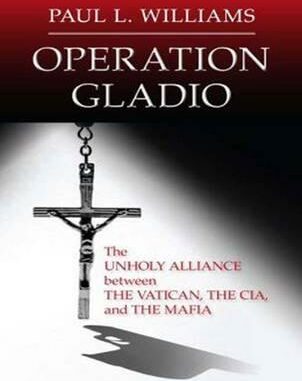

Returning to my NATO pile in the library, I began with Operation Gladio: the Unholy Alliance between the Vatican, the CIA & the Mafia by Paul L. Williams, published in 2015. Williams is knowledgeable about the recent history of the Vatican, an aspect I most wanted to understand. I followed Operation Gladio by diving straight into his latest, Among the Ruins: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Catholic Church , published in 2017. Among the Ruins traces the decline and corruption of the Roman Catholic Church since the changes initiated in the 1960s by Vatican II.

Williams does a good job of describing Operation Gladio and weaving the threads of global political power with transnational organized crime cash flows and related investments that have been uncovered by a series of official investigations, including funding of false flags and covert operations. His description of the decline of the Vatican and the Catholic Church is particularly compelling. The tragedy was not just that the Church was plagued by association with narcotics trafficking, financial corruption and money laundering. Rather hundreds of millions of people who needed a church, a place of faith, a community with global networks and safe neighborhoods were left stranded by a leadership and hierarchy distracted by their global “game of thrones.”

I remember a friend who had left the Catholic Church once telling me that if someone started a new church and all the former Catholics in America joined it would be the largest church in the United States. Williams helps the reader appreciate the extraordinary cultural and human cost of the institutional failure involved.

If you want to understand the Post World War II history of “secret money for secret armies” and the extent to which financial secrecy is an addiction that has devastated global institutions, William’s scholarship makes a useful contribution. As we learn more about the patriots who tried to stop the passage of the CIA Act of 1949 and the subsequent wider opening of the US markets to narcotics trafficking through a partnership of intelligence agencies with transatlantic mafias, it is worth imagining what a different world it would have been if they had succeeded. Indeed, it is never too late to learn from our mistakes. Unfortunately, with FASAB 56, we are headed in the opposite direction – more secret money for secret armies.

Understanding Operation Gladio and the decline of the Catholic Church will help you understand what Bill Moyers meant when he said, “Once we decide that anything goes, anything can come home to haunt us.”

I have more to learn about Operation Gladio – there are more books in the pile!

Buy the Book:

Related Reading: