Original Publication: Fall 1999

The Story of Edgewood Technology Services – (Part Two)

or… How I Lost $100 Million Discovering Who Makes Money Making Sure the Solari (Popsicle) Index Does Not Go Up

by Catherine Austin Fitts

For Other Parts See… The Story of Edgewood Technology Services (Part One)

– The Story of Edgewood Technology Services (Part Three)

In Part One, Catherine Austin Fitts described how, as an advisor for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), she and her company Hamilton Securities had been charged with streamlining the HUD financial portfolio for Secretary Henry Cisneros. Using her experience as a Wall Street investment banker she brought the disciplines and creativity that had ensured her success on Wall Street into what was a decidedly political arena. It did not take her long to realize that she was dealing with a different “operating system” powered by a different set of values than the financial performance criteria dictated for government assets by law.

As she looked deeply into government operations and HUD programs and philosophies she saw obvious simple economies and reforms that would have brought sizeable immediate benefit to taxpayers. But these reforms involved things like bringing computer training to mothers in inner city housing projects. They involved things like upsetting powerful vested interests and entrenched notions that black people were “hopeless.” And they involved training and the creation of learning centers in HUD projects which would have made knowledge accessible to one and all about how the money really works in America.

Just as Fitts was beginning to demonstrate how quickly the Afro-American mothers of HUD’s Edgewood Terrace project in Washington, D.C. could master computer programs, data processing and software design she began to sense the approach of an oncoming bulldozer. That bulldozer, set in motion when Hamilton used its own money to fund a data processing company called Edgewood Technology Services (ETS), would ruin her business and personal finances, endanger her life and try to stop what was described to her as “computers for niggers.”

One reason that the destruction of Hamilton, and of ETS, became a high priority for a variety of interests was that work being done by ETS in the summer of 1996 would tie directly into the Gary Webb, San Jose Mercury News stories about the 1980s CIA connections to crack cocaine in LA.

… THREEE PART SERIES CONTINUES …

Edgewood Technology Services: What Was the Goal?

When my former company, The Hamilton Securities Group, invested in Edgewood Technology Services (ETS) we had three goals:

Outsource Our Data Servicing Work: The first goal was to make sure our growing data servicing needs were met by a reliable team trained to handle sophisticated financial data; Prototype The Solari Investment Model: The second goal was to prototype the use of Internet based tools to incubate “place based” networks of community databanks and small businesses and finance these networks and their communities with stock market equity.

Create Equity Value: The third goal was to create a data-servicing site that could be duplicated in other places; the network would have equity value, resulting in profit to us when we brought in additional investors or took the network public.

Between 1990 and 1995, as we watched American pension funds race oversees to invest in emerging markets abroad, we realized that our retirement savings was being invested in Asia and Eastern Europe as these regions weaned themselves from heavy loads of government subsidy and debt. It seemed to us that the same kinds of opportunities should also exist here in America.

Why not invest America’s retirement savings in American communities as we weaned them off of welfare, HUD investment and other federal subsidies and financing? This win- win-strategy could produce stunningly high equity investment returns for the taxpayer, communities and investors.

Some of our questions included: how much time and investment would it take for on line education to build a workforce that could be highly productive at $8 an hour plus health care and benefits? How fast could that workforce continuously improve their skills to generate additional income and equity value? What tools and incentives–such as stock options–would enhance a community’s ability to generate new businesses and increased income and equity quickly?

We thought the best way to figure this out was to “just do it.” Edgewood Technology Services (ETS) was a group of ten people starting a data servicing company in 1995 after a ten week training program on Microsoft Office Suite. My company, Hamilton, had funded a computer learning center in their apartment building in the Edgewood community in Washington, D.C.to get the ball rolling. Hamilton also paid for the training and initial start up costs of the company.

Edgewood was a good place to start. It was likely going to lose federal subsidy during the then pending welfare and housing reform fervor in Congress. At the same time, institutional investors in downtown Washington and its suburbs could increase their equity values if the inner ring of neighborhoods in the District improved.

Did We Accomplish Our Goals?

Did we accomplish our goals? As far as setting up a data servicing company and fleshing out the rudiments of what was to become the Solari Investment model are concerned- absolutely, yes. Not as far as making money was concerned, though. Hamilton was an investor in ETS for two years.

At the end of that period we transferred our interest (to our initial co-investors and the residents in Edgewood) for $1, offered jobs to those who wanted to join us and started investing in neighborhood stock corporations. This lasted until HUD enforcement efforts, commenced soon after we had demonstrated our investment model’s potential, destroyed Hamilton and its cash reserves and equity value.

Our experience at ETS had persuaded us that investing in a network of neighborhood stock corporations with community databank/data servicing operations was much more profitable than the corporate data servicing model we had in mind when we initially invested.

However, our neighborhood stock corporation model was not well received by vested interests in the corporate, real estate and investment communities. We were beginning to understand that market returns on neighborhood stock corporations would be quite attractive if a way could be found to overcome the ability of “organized crime” to use government enforcement and covert operations to stop us. Our definition of organized crime as including the federal government was just beginning to evolve.

Neighborhood Networks: “Why Give Niggers Computers?”

The initial results from the computer learning center and ETS were so positive that a number of people started to change their minds about HUD’s role facilitating access to on line education. One of the obvious lessons at ETS was that women who were responsible for taking care of children and parents could be a much more productive workforce when they could work and study near their homes. Moreover, learning was much more powerful when families reinforced each other. The seniors and the kids taught each other, and seeing Mom as a highly computer literate person got a woman’s kids very excited about the possibilities of learning. Meantime, the kids could teach everyone and were naturals to master some of the set up and maintenance issues. All of these lessons spoke to the benefits of integrating new technology into residential infrastructures, particularly where they could link with local schools, libraries and businesses.

The first thing that happened was that our efforts to persuade HUD to change the definition of “housing” in some of its programs bore fruit. This meant that $13 billion of annual Section 8 apartment subsidy and $4 billion of annual multifamily mortgage insurance could incorporate computer learning centers in HUD subsidized apartment buildings around the country. One of the more prophetic statements came from Helen Dunlap, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Housing, who took the lead on getting the program approved. She said to me at the time, “You know, if we do this, they will kill us.” Three years later, after Hamilton’s $100 million loss and Helen being run out of government, to her credit she said, “You know they did get us — but it was worth it.”

The concept caught on pretty quickly. The HUD Seattle field office offered to take the lead to promote “Neighborhood Networks ” as the HUD program was known. The effort to reach out to private owners and residents interested in integrating computer learning centers and job training in or near HUD subsidized apartment buildings was popular at the grass roots but less so at higher levels of government where skepticism was strong. HUD Assistant Secretary Nic Retsinas predicted that “Neighborhood Networks” would be the “Hula Hoop of HUD housing.” The field offices, however, embraced the idea and numerous examples of positive results for started popping up around the country during 1996.

Our corporate partners in ETS, a Los Angeles entertainment company, made a video about the opportunity to increase real estate and business values through on-line education, as demonstrated at Edgewood. HUD made two videos about Neighborhood Networks. These and our web sites started to circulate the vision of how to use technology as a tool to align the interests of communities and taxpayers. The essence of these prototypes was what they said about the speed at which people could learn enough computer skills to generate a sustainable wage.

When the training started, one of the social workers at Edgewood predicted that it would take two years for the first group of employees to be productive. After the training program was over, she was asking if members of ETS could teach her and her staff how to use several computer applications. Her boss, Leslie Steen, who ran the not-for-profit management company, corrected her, saying that “those people” could not possibly teach her staff anything. The social worker replied “Leslie, have you been in ETS and seen the things they are doing? They are far better than us and they are really good at teaching computer applications.” Leslie appeared stunned and none too pleased. Leslie’s organization was heavily dependent on subsidies that presumed her tenants were dependent and needed substantial management and services – they needed “keeping.” A pro-market model was not something that appeared attractive in any way.

The most negative reaction was from the HUD Inspector General’s office.

The head of the Inspector General’s audit group, Chris Greer, had been supportive of the idea from the start. He understood that if the people who lived in real estate financed by the taxpayer have no education and jobs, the taxpayers would lose money. So, in late 1995, he showed the ETS video to those in attendance at a large meeting in the Inspector General’s office.

It went over like a dead duck. They hated it. It took me a while to sift through a stream of second hand stories to find out why. Repeated requests to meet with the Inspector General were turned down.

In 1998, as my partners at Solari (an investment advisor we had created to handle money management where the few us remaining work and manage the Hamilton liquidation ) and I were plowing through Hamilton audits and investigations and experiencing physical harassment, I asked some retired HUD IG office staff why the Inspector General had allowed private investors to come at us on things that their office had reviewed, approved and stated on audit were clean as a whistle. One wrote me back and said “The Inspector General old boys’ network could not understand Neighborhood Networks.

Underneath it all was a basic bigotry and class obsession. The program had drawn comments like “Why should we give niggers computers when my kids don’t even have them yet?”

The A/B Stock Plan: “You Can’t Give Them Stock”

The response from the real estate community was about the same.

We had believed that the key to creating equity in a learning company was sustainable learning speed increases. You do a data-servicing project.

The next time you do it, you do it faster. After three times you see an opportunity to add a software tool that will do the task automatically that your client would find useful. You call them and brainstorm. You add it and have them test it. The fourth time around, you modify it for their feedback and so forth. Continuous reengineering involves interactive sharing of knowledge on a trial and error basis within the company and between the company and the customers and the marketplace. In my experience, this learning depends on understanding the economics of what all the players are doing and then participating in the value created. Equity ownership is essential. If everyone in a company owns stock or stock options, they make the effort to understand what generates profit and work together to do so.

Shared equity is one of the keys to shared intelligence in what we call the Solari Investment Model. It is all part of getting into and staying in alignment in an uncertain and changing world.

Gene Ford was the real estate general partner who controlled the investment group that developed the building where ETS began. The idea that members of ETS had access to data about HUD money and about ETS and were going to earn and own stock drove him totally crazy. He used to keep saying to me “You can’t give them stock!” And I would say, “But why?”

That was Sam Walton’s secret at Wal-Mart. All the employees were shareholders.” Gene would say, “They can not be trusted to run the business.” Then I would say, “But Gene, the business is controlled by the A shareholders [A shares are voting shares; employees and most outside investors were going to earn B shares; non-voting shares—this is similar to the stock plan used to control the Washington Post and used by the Chinese and other countries to manage outside investment.

It is also the way Solari has designed ownership in neighborhood stock corporations so that local residents can control the voting shares]. Managers who have experience in managing and building businesses run the business. The process of choosing and promoting people in management is based on team performance over time. The goal of the compensation system and stock ownership is to optimize investment on a sustainable basis. All of this is designed to make us as much money as possible. This is no different than any other business in America. What is the problem?” Gene would look at me, clench his teeth and repeat his mantra.

“You can’t give them stock!”

One of the problems that Gene and Leslie (the head of his not-for-profit development group) and I always had is why we couldn’t refer to Bridget, Mary, Wanda, Lisa, Marvin and all of the ETS employees as something other than “Them.”

Part of the problem was that Gene refused to learn how to use a computer.

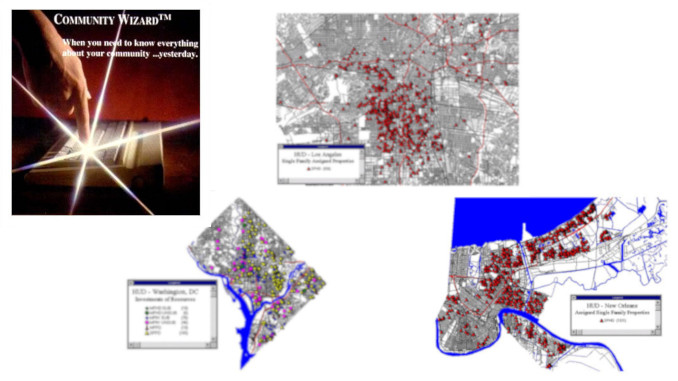

What that meant was that the top performers at Edgewood Technology Services would soon know more about how the money worked on real estate and HUD at the speeds that they were learning and that federal policy was changing, than he did. The speed at which the top performers at ETS were moving on our materials and using geographic information systems to make “money maps” of how money worked in communities astonished even me. Nevertheless, Gene continued to reject all of our offers to teach him how to use a computer and the World Wide Web. And every time I saw him I felt our relationship fray a little more as he would clench his teeth and add once again. “You can’t give them stock!”

Introducing Disclosure and Competition to HUD Programs: “What Do I Care if People Have Education or Jobs?”

Gene Ford was far from the only real estate owner and manager offended by our vision of open access to knowledge and equity based on performance in the marketplace. While ETS busily prepared tools to help understand real estate and mortgage investments throughout the country, including who really owned and controlled HUD’s Section 8 portfolio (something even HUD didn’t know), the battle over how federal housing would be managed in the future was raging in Washington. Battle lines were drawn between traditional Section 8 owners who wanted subsidies to continue without standards of disclosure and competition and conventional real estate investors looking for new opportunities in emerging markets in America.

The way HUD Section 8 subsidized private apartment building programs were originally set up, the developer would line up long-term subsidy contract with HUD. Then, he would take the contract and a commitment for a government guarantee to a participating bank or financial institution that would finance most of the property. Limited partners’ investment in the syndication of tax benefits would fund the rest. The owner, who generally acted as the general partner of the partnership and manager of the property (often under a sweetheart, above-market management contract), profited from up front syndication fees and management fees over time. Limited partners got tax write-offs and then pretty much forgot about the property. They wanted to avoid taxes. When I worked on Wall Street, the accountants would call us all up every December offering us HUD Section 8 tax shelters before our tax year was up. The write-offs were very big because the guaranteed contracts and financing meant that you could depreciate a lot of the value when your investment was tiny. Nobody much cared whether the property was self-sustaining in a market environment, because we assumed government contracts and guaranteed protected everyone but the taxpayer from loss.

The incentives to do a good job for the next thirty years (the usual term of the guaranteed mortgage) were not so wonderful. The landlord controlled the subsidy. If the tenant moved out, she [usually] lost her family’s subsidy.

Meantime, the landlord had often gotten his profit out up front. If the tenant actually got a job, her family might lose its home — their subsidy, and the family was worse off than if there were no job. The system bred lying. Landlords lied about what they were making because of HUD regulations that limited partnership profits. Tenants lied about what they were making to avoid losing rent subsidies, welfare and Medicaid. Economics for both landlord and tenant were determined by a variety of factors unrelated to incentivizing performance. Meantime, many owners and investors could not exit the investment because of tax consequences or regulations of below market rents or above market management fees and rents. One of my partners used to call these deals roach motels because the money went in and it never came out. If the truth is sunlight and darkness is deception then the nickname needs no further explanation. Roaches love the dark. What ETS had done was to show that people and business actually thrive in the sunlight.

The standards of financial accountability and disclosure that corporate law and the Securities and Exchange Commission required of public corporations were unknown in this world. Taxpayers had no access to the financial statements or any performance reports for the near trillion dollar HUD financing and subsidy portfolios.

Given the poorly conceived structure of its programs, HUD experienced substantial defaults on both home and apartment mortgages. In 1994, HUD started to auction these mortgages (which it acquired after default when the guarantees were called) with my company, Hamilton, as the lead financial advisor. As HUD sold off almost $10 billion in defaulted apartment and home mortgages, using sophisticated databases and the Internet for enhanced disclosure on how programs and investments worked, numerous investors and money managers started to see the opportunity to make attractive returns buying and reengineering lower income HUD portfolios. As this happened, interest increased in the opportunity to compete for FHA financed mortgages when and if the entrenched good old boy Section 8 owners were not able to pay them off or when their subsidy contracts were not renewed.

The traditional subsidized players were anxious to keep the subsidy game going for multiple reasons. First, the large ones wanted to divest at a profit in the stock market as the stock market soared in 1995 and 1996.

They wanted time to get their own money out before government policy changed.

They also wanted to use their stock to make acquisitions. Favorable government policies for a year or two more would ensure that their stock price was high and put them in a position to be successful in the acquisition game and in making sure that management’s stock options were worth the most money possible. In addition, many of them were concerned about the tax consequences of mortgage defaults when their long term subsidy contracts matured and the government did not create new ones. Finally, losing control increased the chances that others would see what had really happened in terms of property and money management. Any cases of financial fraud, such as money laundering, loan brokering (deliberately defaulting on large insured loans) or parking covert CIA operations and hiding staff on property payrolls would be illuminated and, if ongoing, ended. The role of the limited partners in the HUD investment partnerships was politically significant. A generation of partners at all the finest Washington and Wall Street law firms, investment banks and accounting firms did not wish to receive tax bills or be exposed as slum landlords, let alone become associated with documented financial fraud and illegal covert operations.

In 1995, I was asked by HUD to call Andrew Farkas, then Chairman of Insignia, the largest manager of Section 8 apartment buildings. Andrew personally assured me that if HUD issued rent vouchers to tenants instead of awarding Section 8 subsidies to landlords for their buildings, the people who lived in his buildings would simply take the vouchers, sell them for drugs and their children would go without decent food. “If you give them [tenants] vouchers, they will simply cash them in on the black market and use the money to buy drugs, ” swore Andrew. The American government had an obligation to make sure that Andrew managed and controlled all the rent money. I warned Andrew, without understanding how prescient my comment was, that if he portrayed poor people this way, then the government would perceive that they were not worth investing any money in.

Dick Ravitch was a colleague from New York who owned several subsidized buildings and served as Chairman of the AFL-CIO Housing Trust. Hamilton had hired Dick as a consultant to help us with our work at HUD. As things turned out, he spent most of his time in Washington lobbying against our position on the Section 8 subsidy funding crisis. One night we had dinner at the Jockey Club, and Dick told me that he was lobbying Congress and the Administration for long term subsidy contracts, directly in opposition to what we had advised HUD. I started to talk about education and jobs in the South Bronx, where one of his buildings was.

Dick said, “If I can get long term government subsidy contracts, what do I care if people have education or jobs?” I thought that about summed up the difference between the two worlds. The non-performance-based guys wanted a “Soviet” model. They wanted no-risk debt financing and subsidy that guaranteed their profits without concerns about performance and thought that, once their subsidy and financing was locked in,, the more stupid everyone in the building was the better for profits.

The performance-based guys, on the other hand, favored learning models and equity financing rewarded all parties for disclosure and collaboration that was focused on creating value. Because the non-performance based guys could not perform as well in the market, their sole strategic option was to rig the game to protect their markets, through any means necessary, legal or not. And that is exactly what they did.

(CLICK TO CONTINUE – Real Deal: Edgewood Technology Services (Part Three) – In Part Three Catherine Austin Fitts describes how the continuing success of Edgewood began to draw attention in more and more influential circles, including the Senate. As this happened, the enemies of Edgewood Technology Services and Hamilton grew more and more determined to kill this threat to their protected money pot. One of those at the top of the list was Harvard University.)