“It shouldn’t work. It shouldn’t be magic. You shouldn’t weep happy and then sad and then happy again. But you do. And I do. And we all do.” ― Ray Bradbury, The Cat’s Pajamas

By Nina Heyn, Your Culture Scout

Foreign black and white movies do not find favor with contemporary American audiences. The 2011 French movie The Artist was an exception but it had to garner 5 Oscar wins including the Best Picture, 152 different awards and 190 nominations before it made about $44 million in the US box office and $133 million worldwide. It also had no subtitles, being a silent movie. Since almost nobody makes black and white movies these days, this is an unusual year when there are two major ones, vying for Academy Awards, and both of them are foreign films with subtitles. For audiences all over the world reading subtitles is commonplace, but American audiences tend to avoid it so this is one more hurdle for these movies to overcome.

The two amazing movies in question – Cold War and Roma – have a lot in common. Both are set in mid-20th century, both are an evocation of director’s family history, and both are imbued with lyrical and dramatic sensibilities of a non-American artist. For that last reason alone, it’s worth taking a closer look at the two movies that show such a different political history that would be portrayed in any typical American drama.

Roma is leading the Oscar pack with countless critics’ accolades and nominations. Directed by Alfonso Cuaron (Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Children of Men, Gravity) it is a trip down his memory lane when he was growing up in Mexico in 1970’s. This not Mexico City of tourist trips to Chichen Itza pyramid, Mariachi bands or fajita restaurants. This is a portrait of a daily life in an upper middle-class family with four boisterous kids, intellectual but a bit lost mother, a scoundrel for a (mostly absent) father, and the unlikely center of this small universe – an indigenous Indian maid called Cleo.

Yalitza Aparicio (a non-professional actress who was a preschool teacher in Oaxaca when she was discovered) shines with every minute of her subtle performance. At first it is easy to dismiss her – almost silent, passive character who goes about cleaning, serving food, putting kids to bed, opening the gate for the father’s car- all the repetitive chores of the day. Then we get used to her quiet presence and get drawn into her world. She was seduced and left pregnant by a youth whose paramilitary sympathies will soon become lethal when a large street riot erupts. She is a silent participant in the family’s ups and downs – a fancy party at a hacienda estate, household’s changes after the father’s betrayal, a child’s brush with death. But even if she seems to be the least important member of this family, it is her quiet love for the children and her stoicism in the face of calamities befalling her that make her the heart of all events. There are big events like the famous Corpus Christi Massacre and smaller events like a fire or near-drowning – all of them are seen from this unique perspective of Cleo’s quiet presence.

For this movie Cuaron handled the cinematography himself in the style of Italian movies – de Sica and Visconti’s neo-realism or even Antonioni’s movies from the 1960’s. Long panoramas, the forgotten palette of grays and whites, each shot composed like a painting or a Henri Cartier- Bresson’s photograph. It’s the look of the movie that tells the story and gives it an ambiance rather than dialogue that is almost non-existent and certainly less relevant than the images. This is a movie as art rather than information – the art that is often forgotten in the rush to communicate important issues or an immature attempt to make the images forceful. Cuaron does not even need much dialogue or any color to make us feel so strongly the emotions of sadness, compassion or nostalgia in this slow evocation of a time and place past.

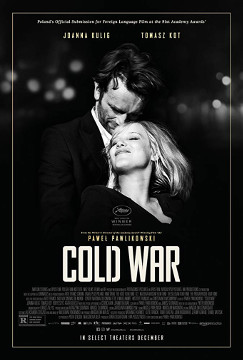

Cold War has a title that is misleading for a viewer who would expect a political drama. Instead this is a story about lovers who literally cannot be together but they cannot be apart either. It starts in the bleak post-WWII Poland – the country has risen from the wartime devastation only to be crushed by a class revolution. Capitalism is out, communism is in.

Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) is a musician tasked by the party apparatchiks to create a folk dance group (modeled on the real and famous Mazowsze folk ensemble) and when he auditions singers in some God-forgotten village, he meets Zula (Joanna Kulig) – a peasant girl for whom this is the only chance to escape to something better. Once the star-crossed lovers get together, there will be some happy moments, but there are no happy endings for people trying to have a normal life in an abnormal world of warring ideologies. Victor decides to escape to the West, Zula does not follow. Even if they do eventually get together in the most romantic Paris of 1960’s jazz, boat trips on the Seine, little black dresses and artistic avant-garde, this will not be enough. Not enough to keep the love going, not enough to stave off the nostalgia of people torn between a seductive but alien West and the bleak but familiar East. Hence the title – the story takes place in the 1950’s and 1960’s – at the height of the Cold War when if you were born behind the Iron Curtain you could not travel to the West, you could not control your destiny, and you paid the price not matter what choices you made.

The movie is inspired by director Pawel Pawlikowski’s parent’s biography. It is his tribute to their lives and the era that is now half-forgotten even if it affected the lives of generations in Eastern Bloc countries. For contemporary audiences, the movie does not even need the political context to seduce as such a romantic and tragic tale of love that crosses the boundaries made by people and circumstances. Wiktor and Zula are the 20th century equivalent of Heloise and Abelard – lovers who are not be allowed to be together and who will have to pay a terrible price. And here is the second meaning of the title – the “cold war” is the nature of this constantly changing relationship between an artist who is blinded by his love and a femme fatale who attracts and pushes away at the same time. The director expresses all this through his beautiful black and white images but also through his music. Cold Waris a kaleidoscope of sounds – Bach’s Goldberg Variations, some moody jazz in Paris, and some amazingly rendered Polish folk music and dance.

Both Roma and Cold War are sad but beautiful films that show what is most important in audiovisual art – not the color, not the language of the text, nor even the text itself – it is the image, music and mood that create those old-fashioned emotions that speak to people regardless of their language, age or a place they come from.

Check It Out!