“It’s said that in Washington the real scandal is what’s actually legal.

The same is true on Wall Street.”

~ Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner, Authors’ Note, These Are the Plunderers

By Catherine Austin Fitts

It’s common to believe that the private equity industry succeeds because it has found a way to make financial extraction and piracy legal. And it is true that the industry has created and made legal many structures and tax benefits that give it tremendous privileges.

It is also common to believe that the private equity industry succeeds because it is run by very smart and aggressive people with good educations, who hire more smart and aggressive people with good educations. And that, too, is true. Note the Ivy League credentials in the selected bios of six top founders or heads of U.S. private equity firms from Wikipedia [hyperlinks and footnotes omitted]. A quick skim of their backgrounds will demonstrate the pattern.

Blackstone ($1 Trillion Assets under Management) TICKER: BX

[Stephen] Schwarzman was raised in a Jewish family in Huntingdon Valley, Pennsylvania, the son of Arline and Joseph Schwarzman. His father owned Schwarzman’s, a former dry-goods store in Philadelphia, and was a graduate of the Wharton School. Schwarzman’s first business was a lawn-mowing operation when he was 14 years old, employing his younger twin brothers, Mark and Warren, to mow while Stephen brought in clients. Schwarzman attended the Abington School District in suburban Philadelphia and graduated from Abington Senior High School in 1965. He attended Yale University, where he was a member of senior society Skull and Bones and founded the Davenport Ballet Society. After graduating in 1969, he briefly served in the U.S. Army Reserve before attending Harvard Business School, where he graduated in 1972.

Apollo Global Management ($598 Billion) TICKER: APO

Apollo was formed in 1990 by Leon Black, Josh Harris, and Marc Rowan, former investment bankers at the defunct Drexel Burnham Lambert.

Black is a son of Eli M. Black (1921–1975), a Jewish businessman who emigrated from Poland as a child (surname, “Blachowitz”) and was the chairman and later majority owner of the United Brands Company. His mother, Shirley Lubell (sister of Tulsa oil executive Benedict I. Lubell) was an artist. In 1975, his father committed suicide. Black received an AB in philosophy and history from Dartmouth College in 1973 and a MBA from Harvard Business School in 1975. He served on the Board of Trustees of Dartmouth College from 2002 to 2011. In 2012, Black gave US$48 million toward a new visual arts center at Dartmouth College.

Harris was born and raised in Chevy Chase, Maryland. He graduated with a degree in economics from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania in 1986 before earning an MBA from Harvard Business School (HBS), working two years at the former investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert in between. He founded Apollo with Leon Black and Marc Rowan in 1990 and helped manage its daily operations until leaving in 2022 to focus on sports investments, done frequently in partnership with David Blitzer.

Rowan was born in 1962. He is Jewish. He was raised on Long Island, New York. He moved with his family to Hollywood, Florida where he attended high school. His father worked in auto-leasing. His mother Barbara was a teacher and a trained concert pianist. He has one sister, Andrea. His grandfather, Emanuel Stein, was an economics professor at New York University. Rowan studied at the University of Pennsylvania. When his father passed away and the family could not afford to pay tuition, the university allowed Rowan to complete his studies and pay whenever he was able. Rowan graduated summa cum laude with a B.S. and an MBA from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

KKR ($510 Billion) TICKER: KKR

The firm [KKR] was founded in 1976 by Jerome Kohlberg Jr., and cousins Henry Kravis and George R. Roberts, all of whom had previously worked together at Bear Stearns, where they completed some of the earliest leveraged buyout transactions.

George Roberts was born into a Jewish family in Houston, Texas. He graduated from Culver Military Academy in 1962 and received the institution’s “Man of the Year” Award in 1998. He attended Claremont McKenna College, graduating in 1966, and the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law, graduating in 1969.

Henry Kravis was born into a Jewish family in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the son of Bessie (née Roberts) and Raymond F. Kravis, a successful Tulsa oil engineer who had been a business partner of Joseph P. Kennedy. Kravis began his education at Eaglebrook School (‘60), followed by high school at the Loomis Chaffee School, where he participated in student government and was elected vice president of the student council his senior year. He attended Claremont McKenna College (then known as Claremont Men’s College) and majored in economics. He was a member of the CMC varsity golf teams for four years and was a member of the Knickerbockers student service organization. He served as his sophomore class secretary-treasurer. He graduated from CMC in 1967 before going on to Columbia Business School, where he received an MBA degree in 1969.

Kohlberg was raised in a Jewish family graduating from New Rochelle High School in New Rochelle, New York. Kohlberg served in the United States Navy during World War II and went on to college and graduate school on the GI Bill. He earned an undergraduate degree from Swarthmore College. He later received an MBA from Harvard Business School and an LLB from Columbia Law School. In 1986, he founded the Philip Evans Scholarship Foundation at Swarthmore.

The Carlyle Group ($381 Billion) TICKER: CG

Carlyle was founded in 1987 as an [sic] boutique investment bank by five partners with backgrounds in finance and government: William E. Conway Jr., Stephen L. Norris, David Rubenstein, Daniel A. D’Aniello and Greg Rosenbaum.

Rubenstein grew up as an only child in a modest Jewish family in Baltimore. His father was a United States Postal Service file clerk, and his mother was a homemaker and then began working in a dress shop when he was six years old. He later recalled: “When I was young, Baltimore was a religiously segregated city. The Jews were in the northwest part of town, and it was very much a ghetto situation. I was 13 before I realized everyone in the world was not Jewish. Up to that point, everyone I knew was Jewish.” Rubenstein graduated from the college preparatory high school Baltimore City College, an all-male school at the time. He then attended Duke University, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and graduated magna cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in political science in 1970. He earned his J.D. from the University of Chicago Law School in 1973, and was an editor of the University of Chicago Law Review.

Bain Capital ($165 Billion)

Bain Capital was founded in 1984 by Bain & Company partners Mitt Romney, T. Coleman Andrews III, and Eric Kriss, after Bill Bain had offered Romney the chance to head a new venture that would invest in companies and apply Bain’s consulting techniques to improve operations. In 2016, the firm named … Stephen Pagliuca and Joshua Bekenstein as co-chairman.

Bekenstein graduated from Yale University in 1980 with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.). He then graduated from Harvard Business School with a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree in 1984.

Raised in the Basking Ridge section of Bernards Township, New Jersey, Pagliuca graduated from Ridge High School in 1973. He attended Duke University where he played freshman basketball before receiving a BA in 1977. He has served on Duke’s Trinity Board of Investors from 2001 to 2008, chairing the board from 2005 to 2007. He is a member of the Campaign Steering Committee and also serves on the board of trustees, serving on the Audit Committee and the Institutional Advancement Committee. Pagliuca received an MBA from Harvard Business School (HBS) in 1982.

TPG Capital ($137 billion)

Texas Pacific Group, later TPG Capital, was founded in 1992 by David Bonderman, James Coulter and William S. Price III. Prior to founding TPG, Bonderman and Coulter had worked for Robert Bass, making leveraged buyout investments during the 1980s.

Bonderman was born to a Jewish family, in Los Angeles on November 27, 1942, and was educated there at University High School. Bonderman studied at the University of Washington, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1963, and at Harvard Law School, where he graduated magna cum laude in 1966. He was also a member of the Harvard Law Review and a Sheldon Fellow. During his time at Harvard, he traveled to Cairo, Egypt, to study Islamic Legal Jurisprudence and Law, and became proficient in various Islamic legal cliques developing a near-native fluency in Modern Standard Arabic.

Coulter was born on December 1, 1959, and raised in a Methodist family, the son of Shirley (née Nagler) and James W. Coulter. His father was a chemical salesman for Chevron. He is a graduate of Shawnee High School in Medford, New Jersey. He graduated summa cum laude from Dartmouth College, where he was also a member of Alpha Chi Alpha. He subsequently earned an MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business in 1986, where he was named an Arjay Miller Scholar.

Price was born in Los Angeles and grew up in Hawaii. He received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University in 1978, and his law degree from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law in 1981.

I underscore the Ivy League because the Ivy League university tax-exempt endowments play a powerful part in the allocation of capital in the United States. In addition, their universities and research centers and their graduates play an important role in driving government policy and business operations in the U.S. The leading Ivy League endowments are at the very heart of what is referred to as “the deep state” and have been for centuries. They represent powerful, private, intergenerational investment syndicates that enjoy the benefits of tax exemption thanks to the universities that support the syndicate and supply an endless stream of talent.

I started to look at the private equity firms when I began to unpack the money laundering and financial management associated with narcotics trafficking in the United States. If you are interested, read my online book, Dillon Read & Co. Inc. & the Aristocracy of Stock Profits. One of the inspirations was the European Union lawsuit against RJR Nabisco for money laundering with global mafia, describing the networks run by RJR before and during the time they were acquired by KKR in a leveraged buyout that is widely thought to have put the private equity industry on the map.

I also looked at private equity firms with inexplicably ballooning investment funds, as billions—then trillions, and now at least $21 trillion—went missing from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Department of Defense (DOD. When large amounts of money disappear from the U.S. Treasury and the New York Fed, and then large amounts of money suddenly and inexplicably appear in the hands of aggressive corporate investors, I get curious.

Are trillions being laundered through the DOD and HUD accounts at the Treasury and New York Fed to reinvest in the fundamental reengineering of American political control and financial wealth?

Investopedia describes a family office as “a private wealth management advisory firm that serves ultra-high-net-worth individuals.” Family offices are designed to serve the members of a family through the generations and often invite associated families and friends in to participate.

I have come to the opinion that the private equity industry is the equivalent of a group of family offices for organized crime—or what Charlie Stephens so appropriately calls “the rackets.” Can I prove my case? Not without hundreds of millions in resources and the capacity to investigate, subpoena, and depose witnesses. So for now, please consider this discussion part of my unanswered questions. Those questions include the following:

- Is private equity primarily a way of cycling funds from a variety of sources—including via a financial coup d’état—that prefer to remain secret for very good reason and best exercise control by owning debt in highly leveraged companies through loyal captured intermediaries who run multiple layers of structured legal entities?

- Are the trends and direction of the industry set by policies determined at the top of the financial system?

- Are they part of policies to move $21 trillion out of the U.S. government or to systematically poison the population and bankrupt labor?

- Are these strategic policies that are intimately connected?

- What is the reason that the private equity industry has long targeted companies that serve people at the middle and bottom of the social and economic ladder? There is a war on the poor, and the way to win that war is to make it profitable to weaken and kill.

Private equity supporters would argue that private equity serves the purpose of shifting capital out of more mature parts of the economy and redeploying it to newer, more productive investment. So, for example, we squeeze capital from nursing homes to reinvest in space. To some extent, I buy this argument. For a great fictional depiction of this dynamic, see one of my favorite movies, Other People’s Money, with Danny DeVito playing the corporate raider. However, I seriously question how much of the repositioning in the large U.S. private equity firms has to do with shifting to productive investment or discovering or applying new technology—and how much has to do with shifting political control and capital and building a control model with illegally sourced capital.

Which brings me to the point I most want to make. I once had a client who was selling a company. I made him promise that he would never discuss his minimum price by phone. When he received the final bids, he called me and said, “You are going to kill me.” “Why?” I said. He replied, “I told my colleagues by phone what my minimum bid was, and that was exactly what I got.” I was stunned and said, “I told you that you would be under surveillance and that the bidding group could be orchestrated to prevent the price from being bid up if they knew your floor.” He said, “I just thought you were being paranoid. I could not believe that we were that important.” I believe my advice could have made him many millions if I had succeeded in persuading him.

As I read between the lines of stories describing scores of private equity transactions, I have serious questions regarding private equity firms’ relationship with private, domestic, and foreign intelligence agencies. Are covert operations—from surveillance to invisible weaponry, bribes, and kickbacks—being used to arrange regulatory support, special treatment, and political favors, and to manipulate and threaten politicians, tenants, vendors, executives, board members, and employees? Do regulators, corporate executives, or research scientists who fail to “play ball” end up being run out of their positions or having car and bicycle accidents?

I remember when I was investigating directed energy weapons in the 1990s. I discovered that some of their alleged applications involved moving tenants out of rent-controlled apartments or making Section 8 tenants sick so they could be upgraded to more profitable assisted housing units. I can only imagine what is happening now, as private equity buys up rental housing throughout the country while significantly increasing rents.

In These Are the Plunderers by Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner, there is a description of the inexplicable and ridiculously profitable acquisition of Executive Life by private equity firm Apollo. One of the participants describes Apollo’s success at blocking a sale to another party:

“Seconds after Marr hung up, another call came through. It was Hartigan, the Apollo lawyer. Angrily, he told Marr he’d heard Garamendi was choosing NOLHGA and wanted confirmation. ‘It was so obvious he had listened in on Garamendi’s short call,’ Marr said years later, ‘my phone had to be bugged.’”

I would also raise the question of the use of entrainment and subliminal programming and other forms of mind control to achieve political goals and market investments and the products and services of acquired companies. When private equity companies reengineer operations, what is the role, if any, of adding questionable or fraudulent tactics into the mix? Something is spreading these tactics throughout American industry.

When I was a managing director at Dillon Read, I used to have a wonderful partner who ran the trading desk. He had his accountant located at a desk in his office at all times. Whenever a trader would book a profit, he would come roaring out saying, “Tell me why I am so lucky.” And that is because, in a perfect competitive market, there is no such thing as profit. It gets competed away. That is why so much effort is made in Washington to create rules that will prevent competitive markets and create oligopolies and monopolies.

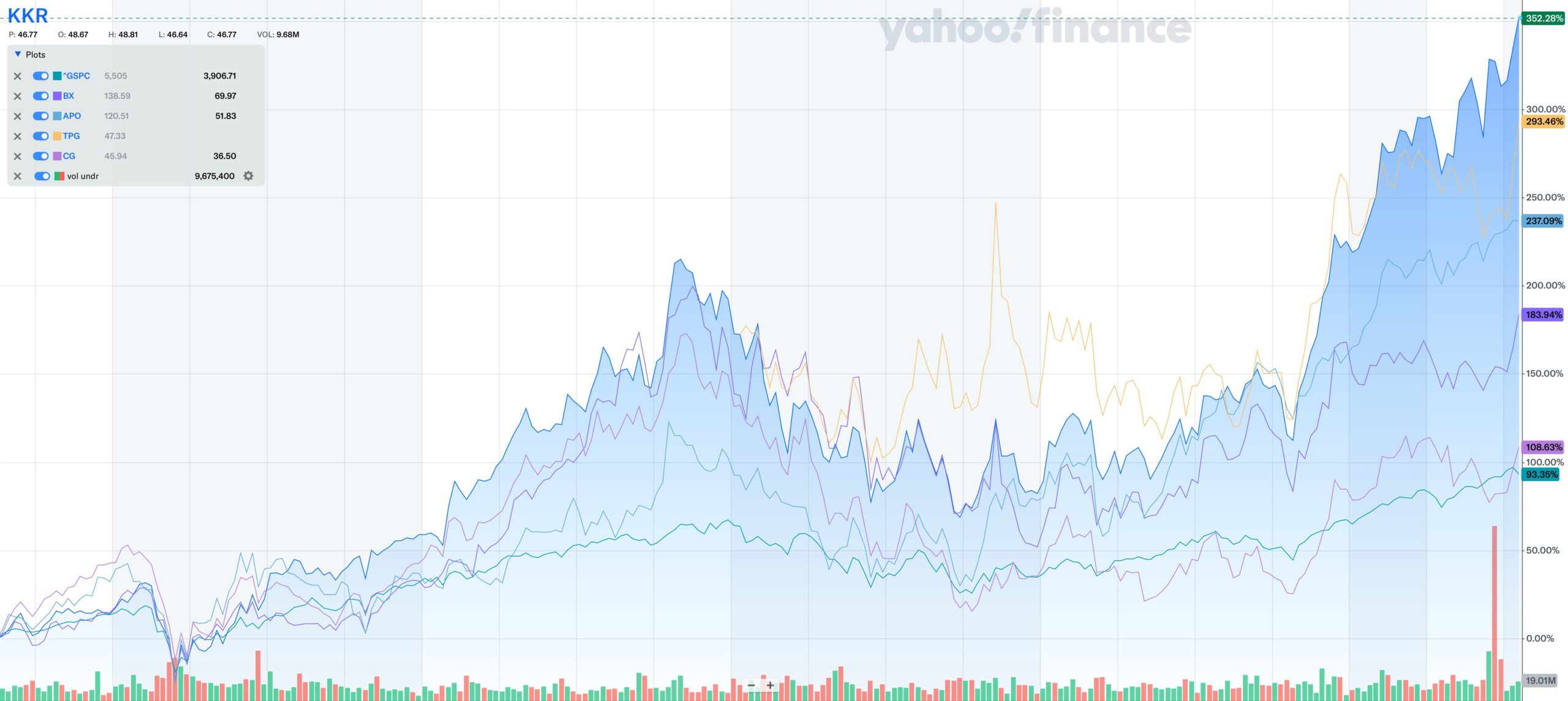

Here is a chart of the stocks of five of the largest private equity firms (Blackstone, KKR, Apollo, Carlyle, and TPG) compared to the S&P since August 22, 2019—the date when the G7 central bankers met and reviewed the Going Direct Reset prepared by a group of central bankers working through the BlackRock Investment Institute. Ask yourself, how is such oversized outperformance possible when a group of investors have no fundamental technological or operating edge?

I mention this issue because our primary problem is not the private equity industry. Our problem is the division of our society into two groups: the majority of the population, and a group of people and organizations who have institutionalized the ability to freely operate in secret outside of the law—whether it is the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) enjoying sovereign immunity and extending it to “systematically important banks” or, as I suspect, private investment and corporate and banking syndicates that use surveillance and covert operations to engineer political and regulatory pressure and compromise prices in private transactions. The result is oversized profits and stock profits.

As we move to understand the plunder underway in America, I do not assume that the large private equity players are lawful and legitimate and somehow miraculously much smarter than the rest of the players.

When I was a little girl growing up in Philadelphia, the mafia ran the numbers and the prostitution. They kept their fights to a minimum and the streets orderly. They started and ran great restaurants and food markets.

I believe the private equity industry is part of a newer and different form of the rackets. As Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock—the firm that manages leading investment positions in all of the publicly traded private equity firms—has bragged, they have a model to grow the economy with a shrinking population.

As we move to navigate an economy increasingly defined by companies squeezed into financial fraud, extractive marketing tactics, and failure by private equity, it is worth bringing more transparency to the fundamental goals of the plunder underway and, most importantly, to the people who are leading it.

Related Reading

2020 Annual Wrap Up: The Going Direct Reset—the Central Bankers Make Their Move with John Titus

Dillon Read & Co. Inc. & the Aristocracy of Stock Profits

Book Review: Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America by Brendan Ballou